The Society Of Friends, or Quakers as they are probably better known, have a large and airy Meeting House (church) in the centre of the city opposite the Central Library.

It was the first time I have ventured inside the building and to be honest I really didn't know what to expect. What I found surprised me - not the architecture, the people. I was greeted by a smiling and helpful member of staff, and made to feel very welcome and at home - not because I was a reviewer, that was a courtesy afforded to everyone - and was in no way rushed. It was a very relaxed, easy atmosphere and a place I could spend as much time in as I pleased with absolutely no pressure.

And before I get to the exhibition itself, there was also a table laid out for all visitors to the exhibits to help themselves to coffee, tea, water, fairy cakes and fresh fruit. An extremely pleasant and in this day and age frankly quite amazing surprise, but most welcome.

The exhibition takes the form of information placards hung on the walls around the two main halls. One downstairs and one upstairs.

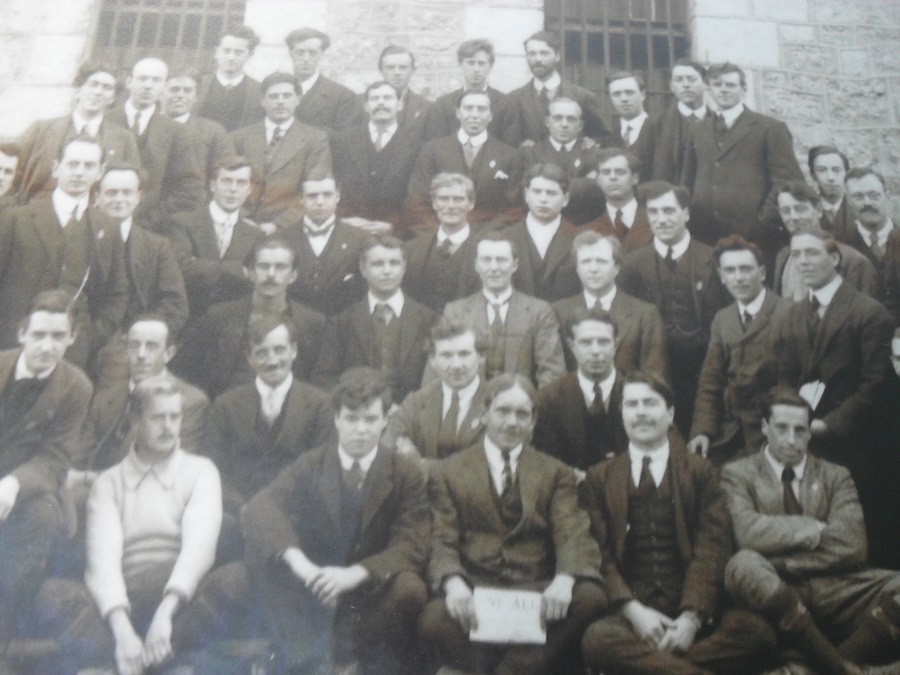

These placards tell the stories of The Quaker Movement, with specific reference to Greater Manchester during the First World War. The writing is exemplified with archive photographs of the people and artefacts.

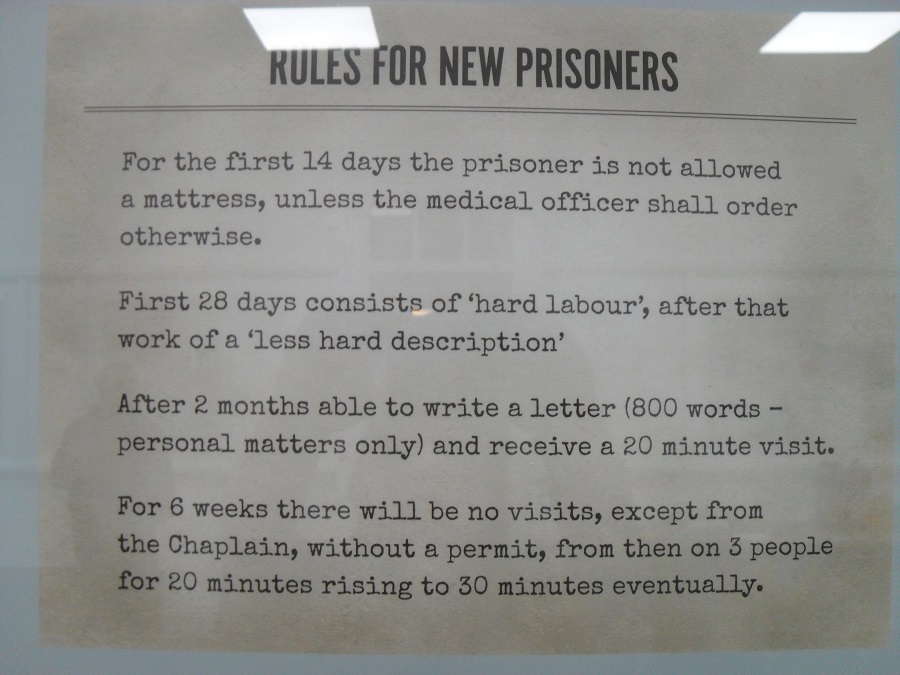

It's a very human exhibition. It tells true stories of real people, and it also makes you think. What exactly was a 'Conscientious Objector'? And how did the government see fit to both test though who said they were, and treat them once proven to be so? Was their treatment of these COs (as they were commonly known) just? Can being forced to join a war and be complicit in, even not directly, the slaughter of fellow humans be seen a just? And if you objected to the governments plans for you, were they justified to throw you into prison, often solitary confinement, and treat you worse than a mangy cur? And then only release you one year AFTER the war was over?

Neither I nor the exhibition takes sides here. It just simply states the facts and delves into the archives to give you a very good idea of how life was for the peace-loving Quakers who were torn between duty to King and Country and their own beliefs. They were being asked to choose between laws which they did not agree with - the laws of war - and the peaceful path, with the stigma they would face upon release and the indignities they had to endure whilst in prison.

My favourite story came from James Garland, (died in 1971) who during the war was sent in a boat to France along with 49 other Absolutist Conscientious Objectors, where their continual refusal to obey orders in a 'theatre of war' led to 35 of these men being formally sentenced to death by court-martial. Their sentences were immediately commuted however to 10 years imprisonment, and were finally released in 1919.

The exhibition is on until Sunday, so I advise all to go and learn something new about the men and women who lived in our community who believed that nothing good can be gained from war and aggression, and these good people stood up for what they believed in; some dying because of their beliefs.

Reviewer: Mark Dee

Reviewed: 9th June 2016